Introduction to Inclusive Design: A Beginner’s Guide was originally published on Springboard.

To understand inclusive design, let’s navigate through the past; In the wake of World War II, large numbers of veterans with mobility-related injuries found that the world around them was built in a way that made everyday activities hard or impossible to operate independently.

Roads and sidewalks, for example, were disconnected by curbs—the six inch drop between the two surfaces made crossing the street excessively difficult for people using wheelchairs or other mobility aids.

Thanks to the advocacy of disabled veterans, the first curb cuts were installed in Kalamazoo, Michigan in 1945. These now-ubiquitous graded ramps connect streets and sidewalks all over the country to accommodate pedestrians who use mobility aids.

The implementation of curb cuts is an example of the social model of disability in action. The social model of disability sees disability as a design problem rather than an impairment, deficit, or health condition. This paradigm understands disability to result from a mismatched, exclusionary interaction between an individual and an environment that is not built to meet the individual’s needs. Inclusive design seeks to prevent these mismatches and create products, services, experiences and environments that offer improved ease-of-use for all.

What Is Inclusive Design?

Inclusive design is a methodology that understands the full range of human diversity as a resource for a better design. Consider curb cuts — this modification benefits pedestrians who use mobility aids as well as the public at large. Whether you’re pushing a stroller, wheeling a bike, carrying groceries, or walking in heels, curb cuts enhance your ability to cross the street smoothly and safely. Modifying the built environment to meet a specific user need often improves user experiences across the board.

In a digital context, inclusive design builds for users with a variety of abilities, backgrounds, and perspectives, striving to eliminate physical, cognitive, and social exclusion. Frequently, exclusion depends on context—an app user who can hear the audio in the quiet of their home might struggle to hear the same audio in a crowded cafe. In this use context, an accessible technology like closed captions—a feature initially intended to serve users who are deaf or hearing-impaired—would improve the user’s experience with the app, even if the user is not permanently hearing-impaired.

While inclusive design strives to lower overall barriers to use, the goal is not to create a single product (or universal product) that meets the needs of an entire population. Inclusive design addresses diverse needs by providing a variety of unique design solutions. For example, the Xbox Adaptive Controller—a compatible, customizable device for gaming and interacting with computers and consoles—enables users to personalize their set-ups according to their needs.

Source: Microsoft

Source: Microsoft

Principles of Inclusive Design

Inclusive design draws on diversity to create accessible options that put users in control. To eliminate points of exclusion and lower barriers to use, inclusive design is guided by principles such as:

- Collaboration. The inclusive design process should be anchored by collaboration with users who experience exclusion. Input from diverse users must guide user research, prototyping, and testing. Design teams should represent a broad spectrum of backgrounds and abilities.

- Flexibility. Inclusive design enables users to engage with digital products in ways that align with their preferences and abilities. Users should be able to perform an action in several different ways. For example, an iPhone user can open an app by tapping an icon on their home screen or by instructing Siri to open the app via voice command.

- Equity. Inclusive interfaces provide experiences of comparable quality to all users. Compliance with legally mandated accessibility standards does not necessarily deliver an equivalent experience—even if a video includes closed captions, this accommodation will not offer an experience that is on par with listening to the audio unless the captions differentiate between speakers via color coding or similar methods.

The Inclusive Design Process

In the design world, process determines product. Retroactive attempts to inject accessibility into a design that was not built around diverse user needs will not yield inclusive solutions. Instead, the design process must center inclusivity and confront biases from the start.

These three pillars guide the process of inclusive design:

- Identify exclusions. Through user research and collaboration, designers work to identify mismatched interactions between the structure of a product and user needs. The design of mainstream products can exclude users based on ability, gender, ethnicity, age, nationality, and more. For example, a product that relies exclusively on manual manipulation of a touchscreen will exclude users who are blind, as well as users who cannot physically maneuver the touchscreen.

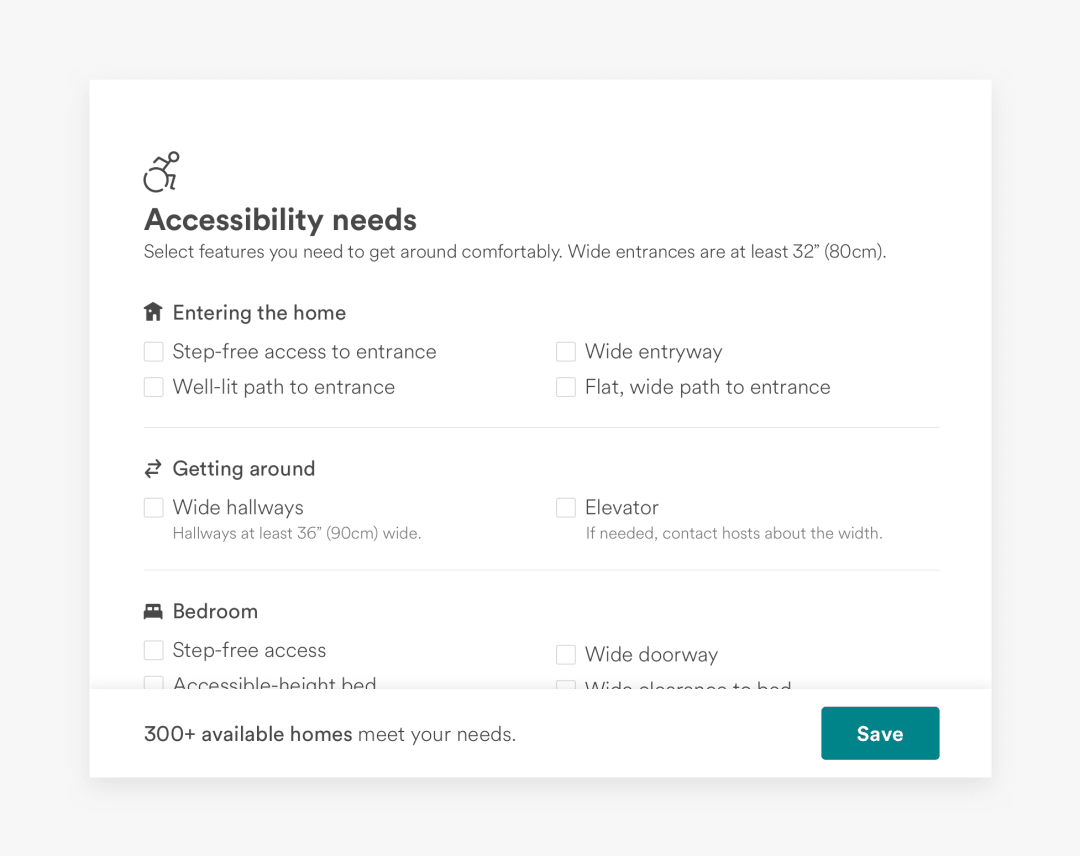

- Learn from diverse users. Observing how users with diverse abilities interface with and navigate existing points of exclusion can provide a jumping off point for the design of inclusive features. Input from excluded users is essential. Feedback from guests who use wheelchairs and mobility aids catalyzed the redesign of AirBnB’s accessibility filter. The platform’s original “wheelchair accessible” option did not specify which accessibility features a listing offered, and did not define wheelchair accessibility requirements for hosts. Guests had to contact hosts to find out if a listing met their needs and weed out misclassified properties. Based on user feedback, AirBnB designed detailed filters that specify accessibility features by room. Now, users can select properties that include features like step-free access, roll-in showers, wide hallways, and more.

Source: AirBnB

Source: AirBnB

- Extend solutions to all. When scaled to serve a broader audience, inclusive design can improve user experiences overall, especially because user limitations are always in flux. A sighted person cannot use a smartphone keyboard while driving, for example, and in this context needs a voice to text option to text or send an email. Web design that prioritizes high color contrast between text and background benefits users with low vision and improves legibility for all users.

Left Image Copy Offers Better Readability

Left Image Copy Offers Better Readability

Source: Accessible360

The Importance of Inclusive Design

Access to technologies that facilitate economic and cultural exchange is vital to equitable participation in our increasingly digital world. Through building products and services that increase and improve access, inclusive design impacts quality of life for millions of users.

A design intended to create equitable access for a person with a permanent disability can also benefit users with situational or temporary limitations. High-contrast screen settings originated as an assistive feature for users who are visually impaired, but also help users who are not visually impaired in outdoor contexts when direct sunlight hampers screen visibility. In this way, designing for accessibility often results in a more creative, adaptable product.

Source: Microsoft

Source: Microsoft

Inclusive design pushes UI/UX designers to consider flows and features from the user’s perspective throughout the entire design process. This facilitates the design of increasingly intuitive products that can be used in a variety of situations—which in turn opens up these products to a broader overall market. In this way, inclusive design methodologies can help aspiring UI/UX designers develop more innovative, commercially viable designs.

In a broader social context, the expansion of inclusive design helps to destigmatize assistive technology and integrate adaptive features into the everyday lives of all users. When designers prioritize inclusive solutions, everybody wins.

Inclusive Design Patterns

Inclusive design solutions encompass a variety of interfaces and features that improve the overall usability of a product. Inclusive design patterns aim to simplify task execution, create clearer layouts, and allow the user to customize their experience.

Let’s examine a few basic contexts in which designers can make inclusive choices to broaden the reach of an app or website:

- Information architecture. A clear, linear hierarchy of information is crucial to streamline navigation. Items should be grouped by relevance and organized by importance. Don’t hide the content of secondary importance—instead, delineate that information stylistically with color or font, or implement a menu.

- Typography and text. To improve readability, use larger text and heavier font weights. Lines should be no more than 50 to 65 characters long for desktop designs, or 30 to 40 characters long for mobile designs. Space lines at 150% or more, and pick fonts like Roboto that have a generous “x-height” (meaning that lowercase letters are close in height to uppercase letters).

- Images and visual content. Emphasize high-contrast design choices to text more legible and distinguish buttons, forms, and other important UI features. Provide alt text descriptions of images that can be read aloud by screen readers. Alt text descriptions can also boost SEO rankings.

How are Companies Using Inclusive Design?

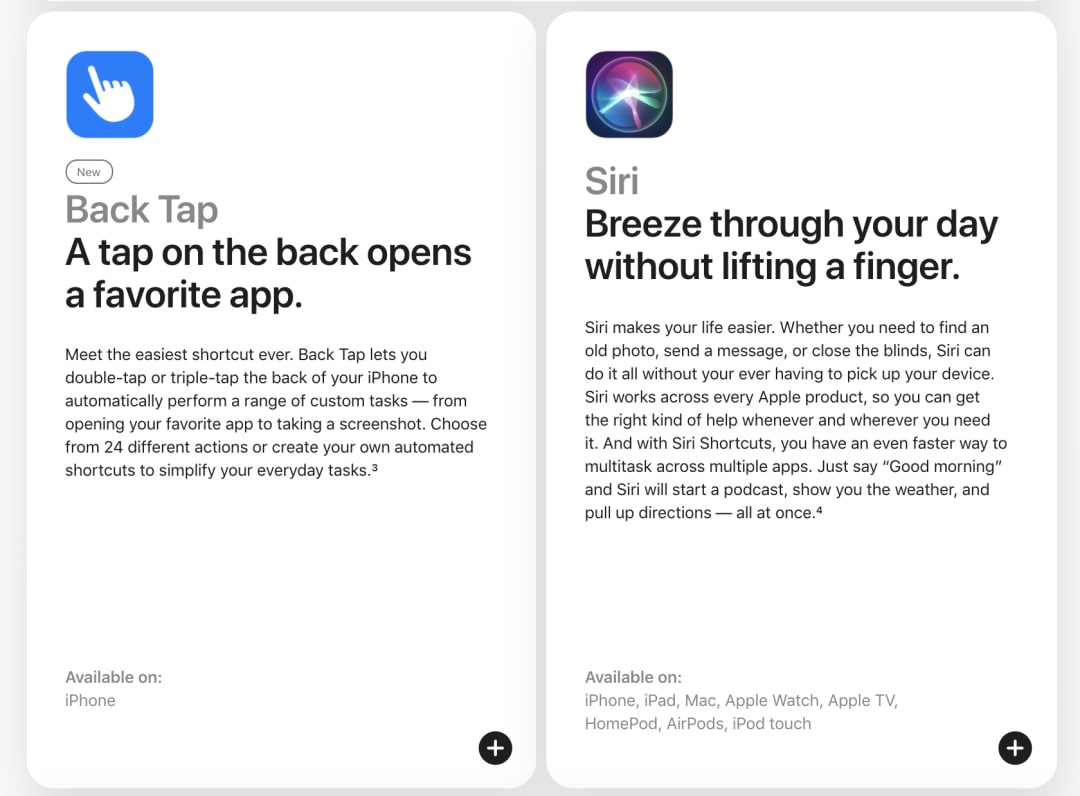

Apple has been a long-time industry leader when it comes to inclusive design. A range of accessibility features allows users to personalize their devices with built-in vision, hearing, cognitive, and mobility features for the entire suite of Apple products. With a feature called Back Tap, iPhone users can simply tap the back of their device to cue apps, take screenshots, and perform other actions.

Source: Apple

Source: Apple

Billed by Apple as “the easiest shortcut ever,” Back Tap enables automatic execution of custom tasks and can be used to replace standard home screen gestures. It can also be used to turn on other accessibility features like VoiceOver, a screen reader that describes what’s happening on any Apple device, allowing users to navigate by listening. VoiceOver utilizes computer vision to describe images aloud, and can identify and describe facial expressions in photos.

In a similar vein, Microsoft’s Seeing AI application narrates the surrounding world as seen through the lens of a smartphone camera. Seeing AI is a free app that is optimized for use with VoiceOver, and can scan barcodes, recognize currency notes, read a handwritten text, and more.

In addition to the assistive technologies created by large companies like Apple and Microsoft, smaller third-party app developers are also creating digital products that focus on accessibility. Ava, a live-captioning app, uses colored text to distinguish between each participant in a conversation, allowing users to follow along with ease. Ava is compatible with iOS and Android, and can be used in professional settings or daily life — the app can instantly caption conference calls or coffee with friends, so long as participants join the conversation on their smart room via an Ava Room link.

These technologies highlight a key takeaway for designers: there is always more than one way to execute a task. Inclusive design puts the user in control, offering options that allow users to interact with products, services, and environments in ways that work for them.

If you are looking to learn UI/UX design and master inclusive design, check out Springboard’s UI/UX Design Course. It’s a 1:1 mentoring-led, project-driven, self paced bootcamp that will take you from beginner to building your first UX portfolio.

The post Introduction to Inclusive Design: A Beginner’s Guide appeared first on Springboard Blog.